The Mysteries of A Single Particle: Exploring Schrodinger's Equation on Particle Systems

By: Aly Ahmed Syed

Despite being relatively new, quantum mechanics has become a frontier field of the sciences. These pioneers have established a new realm of thinking that deviates from our classical mechanics and understanding of physics. One of these renowned figures is Erwin Schrodinger, the developer of the monumental time-dependent equation for a particle system (Figure 1). It has become the cornerstone of understanding subatomic particles and has allowed us to further study the properties of chemicals meticulously through specialized environments. Paying homage to this scientific revelation, by understanding its derivation, application, and limitations, stands to inspire the innovation of scientists that will revolutionize our technologies, energy systems, and our understanding of the natural world.

Figure 1. The Time-Dependent Schrodinger’s Equation.

For centuries, our understanding of physics has revolved around our application of particle systems as a point of mass traveling through two-dimensional space, exhibiting classical properties with quantitative calculations of its position, velocity, acceleration, and momentum. However, this is where the divide between our status quo understanding and the development of the quantum world exists: in the quantum world, a system is treated as both a wave and a particle, challenging the utilization of classical mechanics due to its limitations in quantifying this superposition system.

However, the development of the duality principle, which states that systems exhibit both

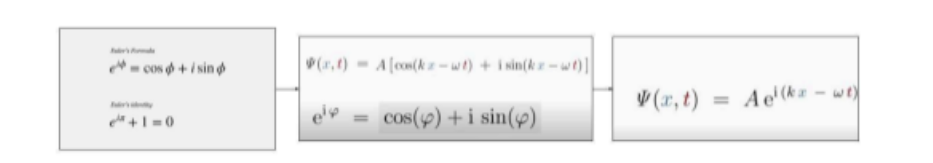

particle and wave-like properties, allows scientists to quantify the particle by using derived mathematics to describe the physical system. This is the foundation of the time-dependent Schrodinger’s equation, as it employs both particle and wave mathematical equations, and applies them to the superposition state of a quantum. The equation consists of four parts: the wave function denoted by the figure psi (Ѱ), the Hamiltonian operator (Ĥ), the imaginary constant (i), and reduced Planck’s constant (ħ). First, the wave function, which utilizes Euler's complex formula, relates it to a sinusoidal function, allowing its application to the wave function (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The fully derived wave function. On the left is Euler’s complex formula, in the middle is the application into the wave formula, and on the right is the wave function.

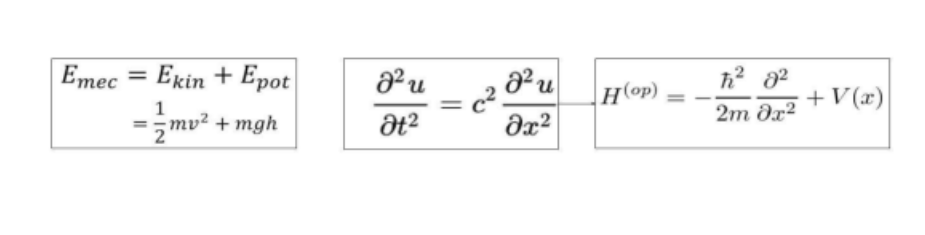

Hence, the application of Euler’s complex function, relating to the wave function, allows for the quantification of the position of the superposition particle by addressing both its particle and wave-like properties combined into this one equation. Secondly, the Hamiltonian operator, which is another set of equations derived from the duality principle, uses both particle and wave-like functions to quantify the superposition system. It relates to the classical mechanical formula of mechanical energy and addresses the wave-like properties through the derivation of the system’s kinetic energy through the one-dimensional wave function (Figure 3).

Figure 3. On the left is the mechanical energy formula for classical physics, in the middle is the one-dimensional wave function, which is used to derive the equation on the right, which is the Hamiltonian operator.

Lastly, one of the last two parts of the equation revolves around the reduced Planck’s constant (Figure 6), which quantifies the momentum of a particle-like system in an atmosphere of wave-like application. The second part is the imaginary constant, which relates the complex aspect of the wave function to its derivation, or evolution of the superposition system.

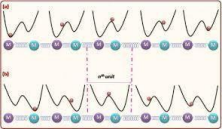

The time-dependent Schrodinger equation describes the evolution of a superposition system by utilizing the duality principle of the quantum particle, exerting both particle- and wave-like properties, allowing for the quantification of position and diverse applications in studying chemical properties, developing new energy systems, and revolutionary technology. One example of newly developed systems that will allow for the unprecedented growth of scientific knowledge is quantum computing. It has been developed and matured through machine learning, which enables better simulations of particle systems, allowing us to deepen our understanding in the fields of computational and theoretical chemistry (Bethel, E.W. et al., 2023). In a study of proton solitons, the time-dependent Schrodinger equation was used (Figure 4).

Figure 4. An example of the influence of proton solitons on transport chains.

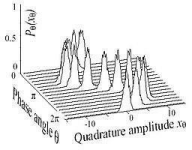

It has allowed for the development of a highly sufficient and stable mechanism of energy transfer in biological systems through the interactions of peptide groups, which are chains of proteins. These protons allow for the existence of a new excitation state of their particles, creating a new wave function of a two-quanta quasi-coherent state (Figure 5), which is then governed through a higher-order nonlinear Schrodinger equation, allowing its properties to be studied.

Figure 5. Graphical representation of a coherent state.

The results help us further understand biological processes such as muscle function, DNA activity, and neural signaling (Kavita, L et al., 2016). Application of the time-dependent equation can also be found during scattering experiments; an example of this is through quantum-controlled collision of hydrogen molecules in a cold inelastic environment in a precisely defined rovibrational quantum state,

which means that the experiment is conducted to examine the transition and levels of its rotational and vibrational energy. Its properties are altered through the use of an SARP (Stark-induced adiabatic passage), which is a coherent optical technique in molecular quantum control to induce transitions between specific rotational and vibrational energy levels.

The data collected from the experiment allows us to set the boundary conditions necessary to solve Schrodinger’s equation, hence allowing us to apply it to theoretical models to better understand molecular interactions (Mukherjee, N. et al., 2023). Therefore, the time-dependent Schrodinger's equation is a ubiquitous formula used to compute various models to help us better understand the quantum particle system, revolutionizing scientific fields and changing our society for the better.

The time-dependent equation, however, still has major limitations, especially when applied to a quantum system with a diverse particle field, and analyzing particles that possess higher momenta due to the uncertainty principle (Figure 6), as it relates the position of a particle’s momentum to its position.

Figure 6. The formulas of the uncertainty principle and Planck’s constant.

Hence, in systems with particles with high momentum, knowing their position becomes a Herculean task. This is demonstrated through the study of an experiment with high-harmonic generation,

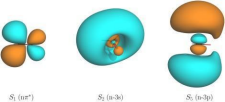

a nonlinear physical process for the production of ultrashort pulses. It was used to investigate the ultrafast phenomena of electrons. However, it was difficult to do so through the electron correlation effect, which shows how the interactions of electrons in complex ways can produce quantum interference. Additionally, the inclusion of the Rydberg State (Figure 7) states that some electrons can move to higher-energy states, making it more difficult to apply the time-dependent Schrodinger’s equations (Coccia, E et al., 2021).

Figure 7. The evolution of a particle under the Rydberg state.

While it is a prominent equation that is utilized predominantly in the scientific world, its application is very case-specific, with a plethora of boundaries to allow for the opportunity to yield better results. However, the efficient future is very near through the application of quantum computing, allowing scientists to replicate the function of the equation on a larger scale, developing better simulations and allowing for our deeper understanding of the natural world.

References

Alexander (Director). (2021). Schrodinger Equation. Get the Deepest Understanding. [Film]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WcNiA06WNvI

Bethel, E. W., Amankwah, M. G., Balewski, J., Van Beeumen, R., Camps, D., Huang, D., Perciano, T., & Rhyne, T.-M. (2023). Quantum computing and visualization: A disruptive technological change ahead. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 43(6), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2023.3316932

Retrieved March 19, 2025, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37930891/ Coccia, E., & Luppi, E. (2021). Time-dependent ab initio approaches for high-harmonic generation spectroscopy. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 34(7), 073001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/ac3608

Retrieved March 19, 2025, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34731835/ Kavitha, L., Priya, R., Ayyappan, N., Gopi, D., & Jayanthi, S. (2016). Energy transport mechanism in the form of proton soliton in a one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded polypeptide chain. Journal of Biological Physics, 42(1), 9–31.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10867-015-9389-9

Retrieved March 19, 2025, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26198375/ Liu, S. (2024). Harvesting chemical understanding with machine learning and quantum

computers. ACS Physical Chemistry Au, 4(2), 135–142.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphyschemau.3c00067

Retrieved March 19, 2025, fromhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38560751/ Mukherjee, N. (2023). Quantum-controlled collisions of H₂ molecules. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 127(2), 418–438. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c06808Retrieved March 19, 2025, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36602238/